A Guide to Sustainable Textile Materials

Updated at 2025-09-04

Want to reduce your climate footprint and contribute to a more sustainable world? We're here to help! Take responsibility for your lifestyle impact starting today.

Three Types of Textile Fibres

Textile materials are divided into three main categories:

- Natural fibres, derived from plants (like cotton and flax) or animals (like wool and silk)

- Synthetic fibres, made from fossil resources, typically oil. Examples include polyester and acrylic

- Semi-synthetic fibres, made from natural sources like wood pulp but processed chemically. Examples: viscose, lyocell and modal

Most conventional synthetic fibres are made from fossil fuels and cause significant emissions – both during production and when washed (as they release microplastics).

Synthetic Fibres

Acrylic

A plastic fibre made from petroleum, requiring large amounts of energy and chemicals. Often used as a wool substitute.

+ Warm, lightweight, cheap

- Easily sheds microfibres, poor breathability, non-recyclable, high chemical use, common in fast fashion

Elastane / Lycra / Spandex

Highly stretchable and often blended with other fibres for flexibility – common in sportswear and jeans.

+ Great fit, retains shape

- Loses elasticity over time, contributes to microplastic pollution, energy-intensive to produce

Nylon / Polyamide

A strong and elastic plastic fibre. Nylon is a specific brand of polyamide.

+ Durable, weather-resistant, inexpensive

- Non-biodegradable, releases microplastics, made with toxic substances

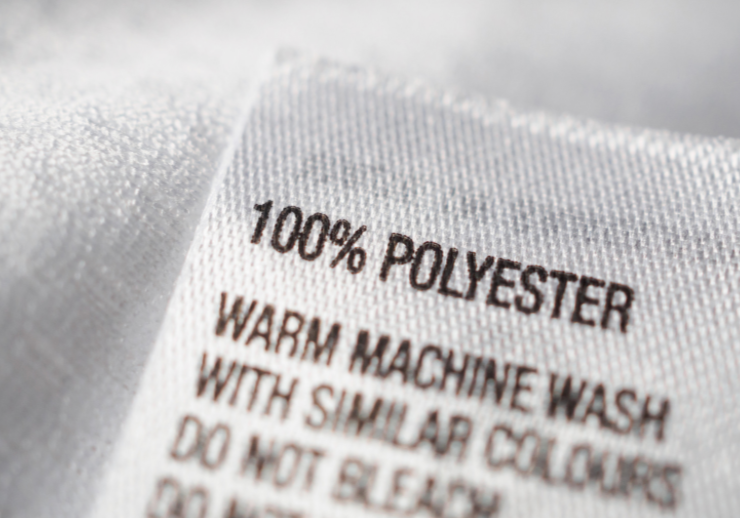

Polyester

The most widely used textile fibre in the world – and one of the most problematic from an environmental perspective. Made from oil and standard in fast fashion.

+ Cheap, durable, quick-drying

- Releases large amounts of microplastics, poor breathability, hard to recycle, energy-intensive

What You Can Do: Synthetic Fibres

- Avoid buying new synthetic garments if possible

- Wash less frequently and use washing bags that capture microplastics

- Air out clothes instead of washing

Natural Fibres – Plant-Based

Cotton

The most common natural fibre in clothing. It can be grown organically but still requires significant water and land.

+ Soft, comfortable, breathable

- High water use, often heavy pesticide use, shrinks easily, low recycling rate

Organic cotton reduces pesticides but may require more water and land.

Recycled cotton has a lower climate impact but weaker fibre quality.

Hemp

Hemp (Cannabis sativa) is one of the most sustainable materials we know. It grows quickly, needs no pesticides and improves soil quality.

+ Three times stronger than cotton, UV-resistant, low water use, fully biodegradable

- Wrinkles easily, coarse texture, rare in retail due to legislation

Flax / Linen

Linen is made from flax stalks. It grows well in cooler climates and requires minimal pesticides.

+ Breathable, cooling, very durable, low water needs

- Wrinkles easily, often needs gentle care

Natural Fibres – Animal-Based

Wool (from sheep)

Wool naturally regulates temperature and resists dirt. Different animals produce different types of wool:

- Angora (rabbit)

- Alpaca (alpaca)

- Cashmere (goat)

+ Temperature regulating, self-cleaning, water-repellent, durable

- Can shrink, often requires handwashing, not vegan

Ethical Concerns

The wool industry faces animal welfare issues, especially in Australia where mulesing is common. This painful procedure involves removing skin from a sheep’s rear to prevent parasites.

New Zealand banned mulesing in 2018. It’s still common in Australia, though some producers are phasing it out.

Alpaca

Alpaca wool is a more eco-friendly alternative to sheep wool. The animals have a low environmental impact, and the fibre is soft, durable and hypoallergenic.

+ Extremely soft, naturally insulating, durable, lanolin-free

- Expensive, hard to trace to sustainable sources

Angora

Comes from Angora rabbits. Though it can be clipped, there are frequent reports of painful fur-plucking in mass production.

+ Extremely soft and lightweight

- Ethical concerns, especially in large-scale production

Cashmere

Comes from goats in Central Asia. Soft and luxurious, but overgrazing by goats contributes to desertification.

+ Lightweight, warm, luxurious feel

- Often causes land degradation, low yield per animal

Silk

Silk is made from the cocoon of the silkworm, usually Bombyx mori, and has been cultivated for thousands of years.

+ Soft, strong, temperature-regulating, biodegradable

- Expensive, often involves boiling live silkworms (not vegan)

Semi-Synthetic Fibres – Natural Raw Materials, Chemical Processing

These are also called regenerated fibres, made from natural sources (often cellulose from wood or bamboo) that are chemically processed into new fibres. The result: soft, silk-like materials – but the process can be harmful.

Viscose

One of the oldest regenerated fibres. Made from wood pulp, often from tropical forests. Production typically uses chemicals like sodium hydroxide and carbon disulfide – harmful to people and the environment.

+ Soft, comfortable, breathable, cheap

- Chemical-intensive, high water use, unsustainable wood sources

Modal

A newer type of viscose, usually from beech trees. Stronger and more durable than viscose, with a lower environmental footprint – especially when sourced from companies like Lenzing (using FSC-certified wood and closed-loop chemical recovery).

+ Durable, soft, holds shape, lower impact than viscose

- Still chemically dependent, not circular

Lyocell / TENCEL™

The most eco-friendly regenerated fibre, especially under the brand name TENCEL™, made from FSC-certified eucalyptus or beech. Manufactured in a closed-loop process that recycles up to 99% of solvents.

+ Soft, durable, moisture-wicking, low environmental impact

- Still reliant on chemicals, slightly higher cost

Cupro, Acetate, Triacetate

Less common regenerated fibres sometimes used in linings or high-end garments. Often have a silky feel but made with hazardous solvents.

New Materials & Innovations

The textile industry is evolving fast, with new materials emerging that offer lower environmental impact. Here are a few examples:

- Piñatex – A leather-like fabric made from pineapple leaf fibres – a byproduct of the food industry. Vegan but contains some plastic for durability.

- Mycelium leather – Made from mushroom roots (mycelium). Brands like Mylo™ and Reishi™ are creating animal- and plastic-free leather alternatives.

- Orange Fiber – An Italian company making viscose-like fabrics from orange peels – leftovers from juice production.

- Spinnova™ – A new fibre made from mechanically processed wood, with no chemicals or water. Still in limited production but could revolutionize the industry.

Recycled Materials

Recycling is a step toward more sustainable fashion, but not without challenges. Many recycled textiles are blends that can’t be recycled again.

- Recycled polyester (rPET) is usually made from PET bottles. It saves energy and resources compared to virgin polyester, but still releases microplastics and isn’t a final solution.

- Recycled cotton requires less water and land than new cotton, but fibres become shorter and must often be blended with virgin cotton.

Circularity – What Happens After We Wear Our Clothes?

To call a textile material sustainable, we must look at the entire lifecycle – from raw material to waste:

- Can it be mechanically or chemically recycled?

- Is it biodegradable?

- Can it compost without releasing toxins?

- What’s the realistic lifespan of the garment?

Synthetic fibres like polyester and nylon are hard to recycle, especially when blended. Natural fibres like cotton and wool can biodegrade but need good cultivation and proper processing. Materials like TENCEL™ and Spinnova™ show strong circular potential – but infrastructure, design and collection systems are needed.

Certifications to Look For

- GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard): The most comprehensive label for organic fibres, covering the entire production chain

- OEKO-TEX Standard 100: Tests final products for harmful chemicals – does not assess production impact

- EU Ecolabel: Official European eco-label with environmental and quality criteria

- Cradle to Cradle: Focuses on circular design and non-toxic materials

- FSC (Forest Stewardship Council): Ensures cellulose-based fibres (like viscose and lyocell) come from responsible forestry

- Responsible Wool Standard (RWS): Ensures animal welfare and sustainable land use in wool production

Most Sustainable?

There’s no simple answer – every material has pros and cons. What matters most is how garments are used, how long they last, and what happens when you no longer want them.

Extending a garment’s life is often the most sustainable choice. The more times a garment is worn, the lower its impact per use. Usage patterns matter just as much as material choice. Also ask yourself: do you need to buy this, or could you use something you already have? Sharing, mending and reusing also go a long way.

Our Sustainability Priorities:

- Use what you have – care for your clothes

- Buy second-hand – choose natural fibres when possible

- Borrow or rent temporary garments

- Choose new items carefully – preferably certified, local, or recycled

- Wash and dry gently – make your clothes last

- Donate or recycle – not the trash! Most textiles can live another life

Summary – What to Choose?

.png)

You Have More Power Than You Think!

By choosing sustainable textiles, you can make a real difference. Clothing production affects the planet in many ways – but there are options that use less energy, fewer chemicals and less water. When you also think long-term, wear what you already own, buy second-hand and care for your clothes – your wardrobe becomes part of the solution. Choosing sustainably isn’t just good for the planet – it feels better too. Together, we can make fashion more sustainable – one choice at a time.

Related content

Here you can find articles and pages relevant to this subject.