Food-related emissions – globally and in Scandinavia

Updated at 2025-10-22

This figure covers the entire food system – from farming and livestock production to transport, processing, packaging, retail, and waste management – and includes a wide range of emissions from both agriculture and industry. In other words, the carbon footprint of food has a massive impact on our planet’s climate and ecosystems.

What affects the environment the most?

Food waste is a climate culprit in its own right, responsible for 8–10% of global emissions – more than the entire aviation sector. Nearly one-third of all food produced worldwide never gets eaten. In practical terms, humanity produces three grocery bags of food, only to throw one of them straight into the bin. Tackling food waste represents a huge opportunity to cut unnecessary emissions while freeing up the resources we need to address both climate and resource challenges. Reducing food waste not only lowers the total volume of greenhouse gases released but also improves the emissions intensity of the food we do consume.

The climate impact of food varies greatly depending on what we eat, how it’s produced, and how we handle it after purchase. Other factors – such as transport distances, storage methods, and production techniques – also play a role. The emissions intensity of different foods can vary dramatically: beef and lamb, for example, have much higher greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram than plant-based proteins. Understanding these differences is key to addressing the environmental impacts of our diets.

In this text, we’ll look at the main sources of food-related emissions, compare the situation in the Nordics to global trends, explore the role organic food can play, and outline the most effective actions to reduce our impact.

Major sources of emissions

Agriculture and land use

The single largest source of emissions in the food system – and a major driver of food’s carbon footprint – is agriculture and land use. This includes:

Methane (CH₄):

Mainly from ruminants such as cattle, sheep, and goats. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a high global warming potential – 28 times stronger than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period – and accounts for a significant share of agriculture’s climate impact.

Nitrous oxide (N₂O):

Released from synthetic fertilisers, manure, and organic soils such as peatlands. Nitrous oxide has an extremely high global warming potential – more than 270 times that of carbon dioxide – making it a critical part of the sector’s carbon footprint.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂):

Produced through deforestation and land conversion to create pasture and cropland. Deforestation is particularly damaging in tropical regions, where forests act as globally important carbon sinks. These land-use changes have a massive impact on food’s carbon footprint.

Other emissions:

From rice cultivation (also a source of methane), burning crop residues, and fossil fuels used in farm machinery. The carbon footprint of food also depends on how different production practices are implemented – for example, regenerative farming and precision agriculture can significantly reduce emissions compared to conventional methods.

Globally, agriculture including land use (the AFOLU sector) accounts for 13–21% of total greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, 2022). In the EU the share is slightly lower, around 10%, but that only covers primary production – when processing, transport, and retail are included, the share rises significantly.

Food waste – a solvable climate problem

Food waste is defined as food that is discarded even though it could have been eaten. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), this amounts to 931 million tonnes annually (2019 data). When food decomposes in landfills without oxygen, it produces methane, further worsening its climate impact and adding to the overall carbon footprint.

However, the climate cost of food waste is not just about methane. All the energy, water, and land used to produce, transport, and package that food is also wasted. Halving global food waste could reduce emissions by an estimated 4–5 gigatonnes of CO₂-equivalents per year – up to 9% of all emissions – representing one of the most impactful ways to shrink our collective carbon footprint.

In Sweden, around 1.3 million tonnes of food and drink are thrown away each year, according to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency – almost 130 kilos per person. Most comes from households, followed by the food industry, retailers, and restaurants.

-3.png)

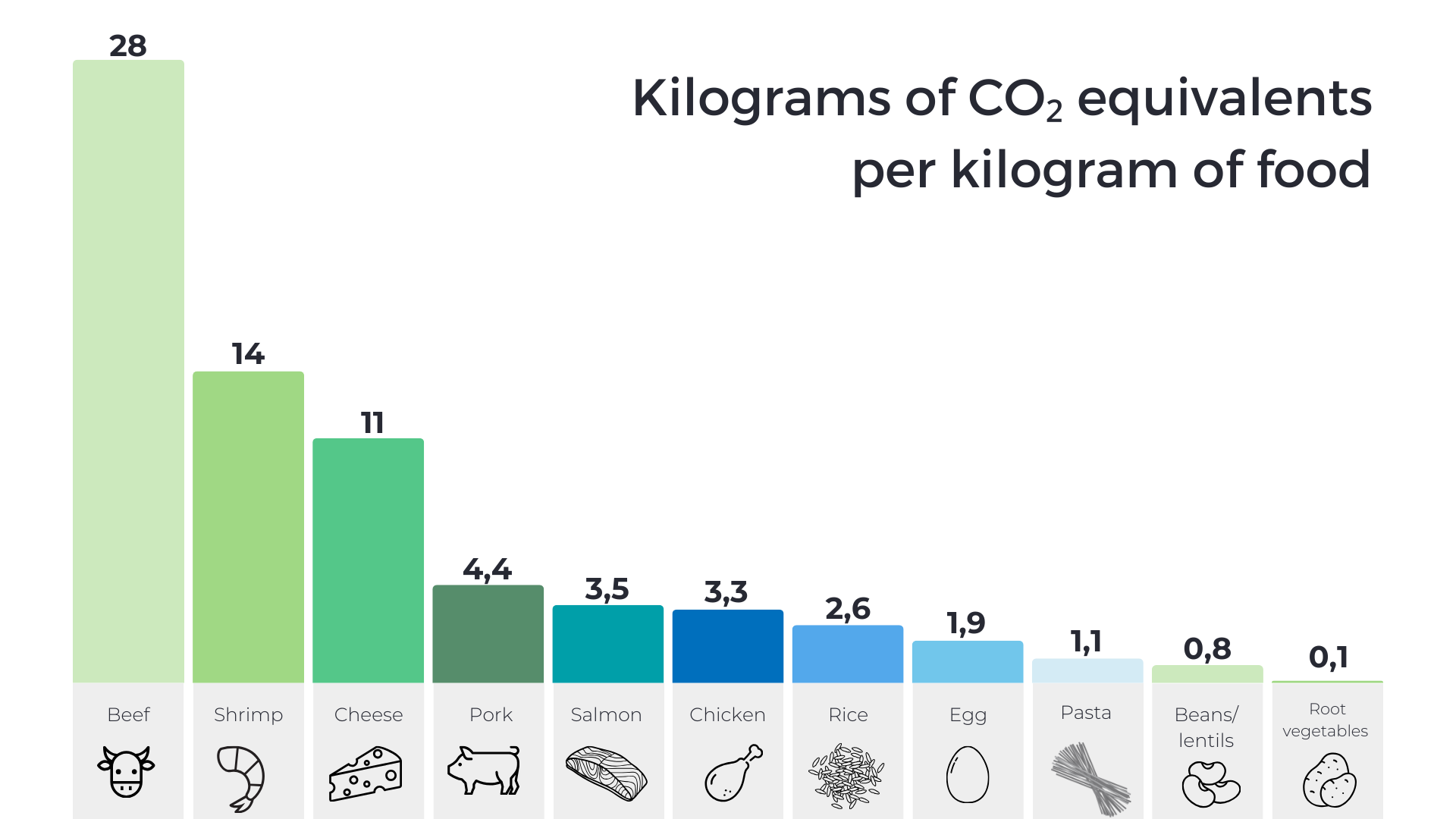

Emissions by food category

Different foods have different climate footprints, often depending on how much land and resources they require and the emissions released during production.

Food - Emissions (kg CO₂e per kg product)

- Beef ~28

- Lamb ~20

- Shrimp ~14

- Cheese ~11

- Pork ~4.4

- Salmon ~3.5

- Chicken ~3.3

- Rice ~2.6

- Eggs ~1.9

- Pasta ~1.1

- Beans & lentils ~0.8

- Potatoes & root vegetables ~0.1

Source: WWF Food Calculator

These numbers clearly show that animal products generally have a higher climate impact than plant-based foods. Meat from ruminants such as cattle and lamb is particularly land- and methane-intensive, making it a major driver of climate change.

Plant-based proteins, such as beans and lentils, can have up to 30 times lower emissions per kilo than beef. By making small changes – for example, replacing some red meat with plant-based options or sustainably sourced fish – we can collectively achieve much better climate outcomes.

Making good choices isn’t just about reducing meat consumption – it’s also about choosing meat from more resource-efficient, lower-impact systems, and combining this with crops that support biodiversity and soil health. In this way, both livestock and crop farming can be part of a more sustainable food system.

Plant-based diets and reducing animal products

Research published in Science shows that a global shift to a fully plant-based diet could cut food-related emissions by up to 49% and free up billions of hectares of land for natural ecosystems. Such a shift would dramatically lower the food carbon footprint of the average person and reduce the environmental impact of agriculture overall.

This doesn’t mean everyone needs to go vegan – even small reductions in meat and dairy products can make a significant difference. Switching from beef to chicken can halve the GHG emissions from a meal, and swapping beef for legumes can reduce them by over 90%. Because meat and dairy products typically generate more greenhouse gases per kilogram than most plant-based food products, adjusting our food choices is one of the most effective ways to reduce emissions and shrink a diet’s carbon footprint.

In Scandinavia, there’s a clear trend toward more plant-based eating, but meat and dairy consumption remains higher than the global average. This means there’s still substantial potential to cut GHG emissions and limit climate impacts here – especially from high-emission foods linked to land use change, such as beef production that drives deforestation.

Organic food and its environmental impact

Organic food is grown and produced according to rules that limit or ban the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers. The aim is to promote biodiversity, maintain soil fertility, and use resources more sustainably. While organic methods focus on improving soil and ecosystem health, their environmental impact must also be weighed against yield and efficiency considerations.

The goal is to minimise chemical inputs and create a circular system in which production residues are returned to the soil. This helps reduce negative impacts on land, water, and ecosystems, and can in some cases lower a farm’s food carbon footprint.

Benefits of organic farming:

- Reduced chemical use: Most synthetic pesticides are banned, reducing the risk of chemical runoff into water and soil. This particularly benefits pollinators and other species essential to fruit and vegetable production.

- Greater biodiversity: Studies show that organic farms often host more species of plants, insects, and birds than conventional farms.

- Soil health: Green manures, diverse crop rotations, and less soil disturbance improve structure and carbon storage.

- Animal welfare: Organic livestock production requires more space, access to pasture, and the ability for animals to behave naturally, improving welfare.

Challenges with organic farming:

- Lower yields per hectare: Organic crops often produce less than conventional ones, potentially requiring more land to produce the same amount of food. If this land comes from natural ecosystems, it can increase CO₂ emissions and pressure biodiversity – a key factor in the environmental impact of any farming system.

- Emissions per kilo of food: Lower yields can mean higher emissions per kilo for some organic products, especially animal-based foods. This can raise a diet’s carbon footprint if meat and dairy products remain a large share of consumption.

- Transport and distribution: Organic products may be transported long distances to reach markets, increasing transport emissions if logistics aren’t efficient.

Nordic examples

In Sweden, over 20% of farmland is organically certified – one of the highest shares in the world (Swedish Board of Agriculture, 2023). Dairy, eggs, and cereals dominate organic categories, but fruit and vegetable production has also increased in recent years. Organic dairy farms often use less fossil energy and store more carbon in pastures. However, emissions per litre of milk don’t always fall compared with conventional production – feed production, animal efficiency, and farm energy systems all matter.

Organic food offers clear environmental benefits when it comes to chemical use, biodiversity, and soil health. For maximum climate benefit, organic farming should be combined with reduced meat consumption, smarter farming techniques, and measures to minimise food waste. When consumers choose organic and producers adopt practices that make the best use of residues and local resources, organic food can help lower the food carbon footprint while contributing to more sustainable food systems in the long term.

Transport, seasonality, and local food

Many people believe that “food miles” are the biggest part of food’s climate impact – but most life cycle assessments show that transport emissions usually account for less than 10% of the total. Production – especially of animal products – is the dominant factor in both greenhouse gas output and the overall carbon footprint.

That said, local and seasonal food still matters. Seasonal vegetables from nearby can have much lower climate impacts than imported ones, particularly if imports come by air or require energy-intensive greenhouse production. For example, asparagus flown in from another continent can result in several kilograms of carbon dioxide per kilogram of produce, compared to a fraction of that for the same crop grown locally in season. Choosing local and seasonal options can therefore be a simple, effective way to reduce emissions linked to your diet.

Policy, innovation, and future solutions

Cutting food-related emissions requires both individual and systemic action. Some growing trends and solutions include:

- Plant-based alternatives: Oat milk, pea-based proteins, and plant-based meat substitutes are becoming more widely available and popular.

- Lab-grown meat: Still in its early stages, but could reduce the need for land and livestock in the future.

- Circular food systems: Recycling nutrients from food waste back into new crops, for example through biogas production.

- Sustainability labels: Schemes such as KRAV, EU Organic, and Svenskt Sigill Climate Certified help consumers choose lower-impact products.

- Public procurement: Municipalities and regions can set climate criteria for food in schools, healthcare, and elder care.

Summary

The climate impact of food is one of the most complex – yet most actionable – parts of our total emissions. Globally, the food system accounts for around a third of greenhouse gas emissions. In the Nordics, emissions per person are somewhat lower than the global average, but still high – and our diets, especially high meat and dairy consumption, offer major opportunities for improvement.

By eating more plant-based foods, reducing food waste, choosing organic when possible, and supporting sustainable production methods, we can all help reduce food’s climate impact. At the same time, we need political measures, research, and innovation to make sustainable, climate-friendly choices easier and more accessible.

Food is more than nutrition – it’s one of the biggest keys to a sustainable future.

Related content

Here you can find articles and pages relevant to this subject.

- Greenhouse gas emissions from agrifood systems. Global, regional and country trends, 2000–2022

- IPCC (2022) – Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change – Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report

- UNEP / UNFCCC (2021) – Food loss and waste account for 8–10% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions

- Naturvårdsverket - Livsmedelsavfall i Sverige (in Swedish)

- WWF Food Calculator (in Swedish)

- Stockholm Resilience Centre (2019) – Nordic Food Systems – Four Future Scenarios

- Nature (2021) – Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food, 2, 198–209

- Jordbruksverket – Ekologisk produktion (in Swedish)

- Science (2018) – Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987–992

- UNEP - Emissions Gap Report 2024